Fijian Thamakau Project:

A semi-replica sailing canoe

THE DREAM REALIZED

In the course of a recent vacation (the Bishop Museum, Hawaii) and research (the Canadian Canoe Museum in Peterborough, Ontario) I've seen two beautiful Fijian outrigger sailing canoes-- or thamakau . Both were rather small (14-15' long), and both left me with a profound and unexplainable need to build one, and learn how to use it. Armed with A.C. Haddon & James Hornell's "Canoes of Oceania" , and photographs of the two canoes, I set to building a semi-replica of a thamakau. ( "Canoes of Oceania" is available from the Bishop Museum, having been re-printed many times since the late 1930's.)

The Construction. . .

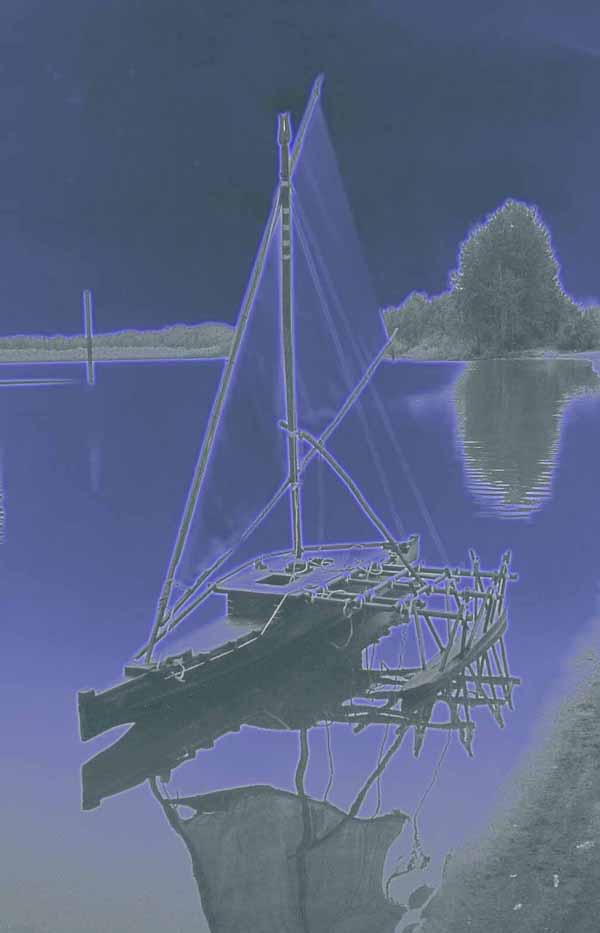

I started with a 10" long model, but promptly moved to the full-scale canoe. In lieu of using a dugout main hull with sewn plank sides, I used the construction method I was most familiar with: Skin on frame-- the skin being polyester,sealed with a two-part urethane coating. The frame is depicted below, having been made from recycled baidarka gunwales, ash ribs, and pine stem boards.

The fore and aft decks are marine plywood, and the turreted deck in the middle is of cedar boards, leftover from a fence project. The mast is a tree I found on a beach on Whidbey Island. For a sail, I used a canvas tarp from Home Depot, and hand sewed the edges. I think the total cost of this canoe was about $80. My canoe is 14'6" long, and the main hull is 12" wide. This vessel does not tack per-se, but instead 'shunts:' The outrigger is always kept to windward, so the direction of the canoe's travel is reversed requiring the mast to be re-angled and the heel of the yard (and the rudder) being carried to the other end of the canoe. The photograph below shows the block that the mast pivots on-- the mast's angle is adjusted with running stays depending on which direction you are sailing: This canoe has no front or back, per-se; it is symmetrical.

The canoe has not yet been launched, so I do not have any experience with this sort of sailing rig yet. Truth be told: I have no idea what I am doing, but what I do have is a strong sense that I am about to learn something. . . .

The Launching . . .

I launched the thamakau in squally weather with shifty gusts at Lake Vancouver, Washington-- hardly optimal, especially for someone who has no idea what he is doing. Only my brother Don was present; Apologies to the several people (Dan, Brian, etc.) I invited to the launching: I was very nervous and unusually insecure, and felt I should get a sense of things before 'going public.' Upon sliding the outrigger into the water and clambering aboard, it felt so light and graceful-- how strange to be atop such a fine boat. I have built 43 kayaks, but to ride atop something seemingly just as agile was an entirely different feel. My brother inquired as to its stability. I knew it was infinitely more stable than any of my kayaks because of the outrigger; I yelled to him "Its solid!" and then promptly flipped over and took a swim. I had sunk the outrigger, and followed it down. You can't 'know' anything when trying something new. I flipped the canoe a few more times before getting a feel for it. I had mis-interpreted the purpose of the outrigger-- it will float, but it is primarily a counterweight when sailing. Before ending the launch session, I thought to at least get in a short downwind run with the sail up, which I did-- good heavens, this boat flies! And then I flipped it with the rig up. Can failure be empowering? Well, I think I failed making the thing work properly, but I was empowered to think that I may yet-- and will.

Learning the ropes: Haul in the halyard!!!

Glory!

%#$@%^&! !

A few days later, I took the canoe out again. An entirely different experience this time: Light winds gently increasing during my two hours out. Where I hadn't shunted a once during the launching, this day I shunted 8 times or so. Everything worked perfectly-- no tipping over at all, and I only dropped the boom in the water once while shunting. One improvement (of several) I made after the initial launch was to rig a rudder attachment. I used a single-blade paddle-- a replica of a Koniagmiut qayaq paddle. Upon sailing the second day, I discovered I had absolutely no need for it at all as a steering method-- the canoe is extremely responsive to weight shifts, and I found I could sail a full circle just by repositioning my body: Turn right? Just lean forward!

I ask visitors if they would like to see my new sailboat. They say "yes," and smile, anticipating what they they envision and expect a sailboat to look like. And then they see it. . . .

During the second voyage of the thamakau, I chanced upon a fellow in his newly launched boat: A Louisiana Pirogue-- with an electric motor. I believe he was South Asian, and it struck me as odd to see a South Asian in a Creole Boat in Washington State--- but then I'm an Oregon Jew in a Fijian Outrigger. . . how odd is that?

Further Adventures. . .

As of June 30th, I've sailed the Thamakau a total of seven times. Each time out brings more knowledge, comfort, and of course problems. Lake Vancouver is a fickle lake, wind-wise. Any outing there this time of year is pretty much guaranteed to bring a 180 degree wind-change, with a long dead-air period, sandwiched between strong winds and foot-waves. The mile course I regularly sail can take 1-3 hours-- sometimes the last 1/4 mile taking two hours!

On the Columbia-- photo by John Kohnen.

One day, I confronted my worst fears head on. I know that to let the outrigger wander to the lee side is to invite the sail to pin against the mast. This of course harnesses the power of the wind to turn your canoe upside-down. Sailing close to the eye of a good 20mph wind, I must've blinked, leaned forward-- or perhaps the wind shifted slightly. . . Anyhow, the knock-down happened very fast. I remember thinking "release the halyard!!!," but before I knew it, I was sitting on the bottom of my canoe, pondering my predicament of soggy tangled lines, a flooded boat, and a canvas sail underneath the whole mess. Even more ponderous was how I managed to end up sitting on the up-turned keel of my canoe without getting a drop of water on me!

Fortunately, the canoe had dis-masted; the mast-head was coated with gray, slimy mud. I righted the canoe by leaning over the hull, and grabbing the fore-to-aft bars on the outrigger booms, and leaned back hard: The canoe slowly righted. I had a hand-pump, and quickly pumped the hull, trying to gain headway over the waves that kept sloshing in. No avail here, so I swam around the boat, gathering the sail, mast and rigging, and set it on top of the outrigger-float, so as to create a bit of leverage lifting the hull as I pumped like crazy. It worked, and soon the canoe was empty. Re-stepping the mast was not too difficult, though I did have to cut and re-tie the halyard, as it was all tangled up, and I was impatient. I soon sailed away-- I survived my first deep-water knock-down, and, well, sailed away.

Sailing on the Columbia River, June 21st, 2003. Photograph by John Kohnen.

Other experiences have been running downwind at a tremendous rate-- canoe pitching, and ropes and sail straining. I dragged my leg to slow it all down-- too scary, but incredibly exciting. A rudder or paddle is required when sailing down-wind, I've found. Shunting in rougher water is quite scary. I have to sit beam-on to the steep wind-waves while shunting, and the canoe gets rocked around vigorously. It's hard to stand up during this, much less while carrying a big sail around.

I got to sail the Thamakau at a wood-boat messabout on the Columbia recently. It was cloudy, rainy, and occasionally quite gusty. The canoe did fine, though I almost flipped it in the middle of the river. I recall a gust of wind, and while I slacked the sheet-line, I also remember leaning way out trying to push the outrigger down-- it must've heeled at least 45 degrees. It happens so fast, but sure as I didn't go ass-over-teakettle, I must have reacted in an appropriate manner. While landing after this near-upset, I flipped it in chest-deep water. I sort of wanted to fly the outrigger and really max-out its performance. Instead, the canoe maxed-out my performance.

An especially nice treat was to see my Thamakau on the water, being sailed in good wind. Don Minnerly took it out for a spin. He's a very experienced sailor, but shunting was new to him. He dry-land shunted a few times for practice, and then took it out. I was as nervous as I'd be if I were on the canoe, but Don did fine, even in the increasing wind.

Modifications. . .

I've made several modifications during the course of this canoe's lifespan. First, I changed the mast-head shape to one that wouldn't fall apart all the time. Both of these shapes can be seen in the photos above. I also cut 12" of length off of the foot of the yard. I think I did this for aesthetic reasons, but it does sail better. . . or perhaps I sail better now. The most significant change was to add 10" of length to the outrigger booms, essentially making the outrigger float 10" further out. This has GREATLY added to the stability of the canoe, and I am much more comfortable flying the outrigger on a beam-reach.

Post-Script

A friend of mine interested in outrigger canoes (Brian Schultz) recently built a Hawaiian-style sailing canoe-- also built 'skin-on-frame.' His canoe turned out to be much more practical than mine-- more stable and roomy, and more seaworthy. The frame is depicted below. Many more photos can be seen on his web-page: CAPE FALCON KAYAK

Brian Schultz's Outrigger Sailing Canoe, Manzanita, OR, 2004